NASA’s Lunar Flashlight — a small spacecraft to measure water ice in dark craters near the moon’s poles — will now launch as a piggyback payload on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket late this year after delays caused it to miss a ride on the agency’s Artemis 1 mission.

Barbara Cohen, the Lunar Flashlight principal investigator at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, confirmed the new launch arrangement for the mission last month during the Lunar Surface Science Workshop, a meeting of researchers planning scientific investigations for future moon expeditions.

Lunar Flashlight will ride into space with a commercial moon lander built by Intuitive Machines, a privately-held company based in Houston that NASA has contracted for at least three robotic lunar landing missions through the agency’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services, or CLPS, program.

The first CLPS mission by Intuitive Machines, known as IM-1, will launch from pad 39A at the Kennedy Space Center on top of a Falcon 9 rocket. A recent update to a public launch schedule on NASA’s website shows the IM-1 mission is scheduled to lift off on Dec. 22, then land on the moon several weeks later, using Intuitive Machines’ methane-fueled Nova-C lander to deliver NASA experiments to the lunar surface.

IM-1 was originally scheduled to launch in 2021 when NASA awarded Intuitive Machines a $77 million contract for the mission in 2019. Intuitive Machines contracted with SpaceX for the launch of the IM-1 mission.

The Lunar Flashlight spacecraft, with a total weight of about 30 pounds (14 kilograms) at launch, will take advantage of excess payload capacity on the Falcon 9 rocket carrying the IM-1 moon lander.

Lunar Flashlight was previously assigned to launch on the first flight of NASA’s huge Space Launch System moon rocket. NASA selected 13 CubeSat missions, including Lunar Flashlight, to ride on the first SLS flight, known as Artemis 1.

Lunar Flashlight was one of the three CubeSat missions that weren’t ready in time to be integrated onto the SLS moon rocket before it was closed out for the Artemis 1 test launch.

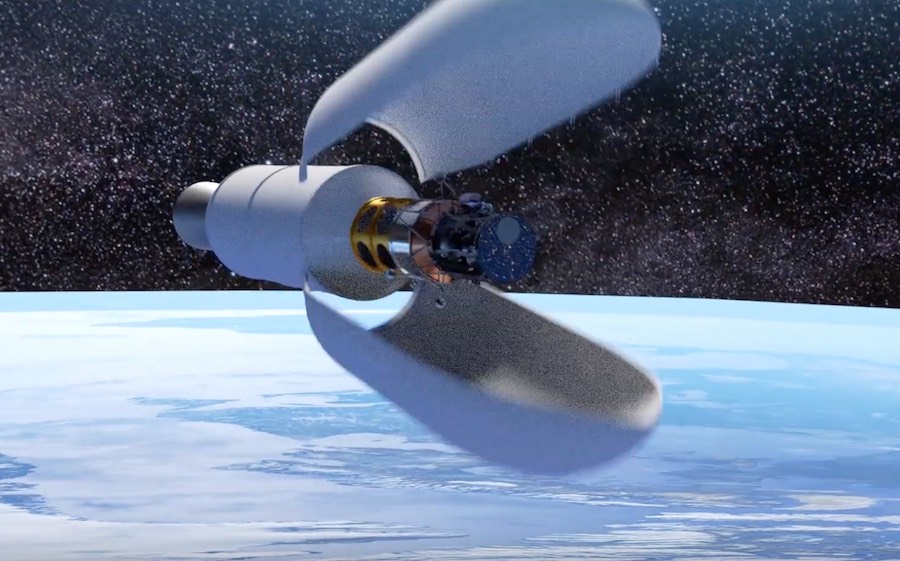

The Lunar Flashlight mission, led by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, is designed to orbit the moon and shine infrared lasers into permanently shadowed craters near the lunar poles. An instrument on Lunar Flashlight will measure the light reflected off the lunar surface, revealing the composition and quantity of water ice and other molecules hidden on dark crater floors.

A NASA spokesperson said last year that issues with the original propulsion system for the Lunar Flashlight spacecraft forced managers to switch to an alternative design. That slowed development of the mission, and coupled with effects from the COVID-19 pandemic, prevented the spacecraft from being ready for integration with the Artemis 1 rocket.

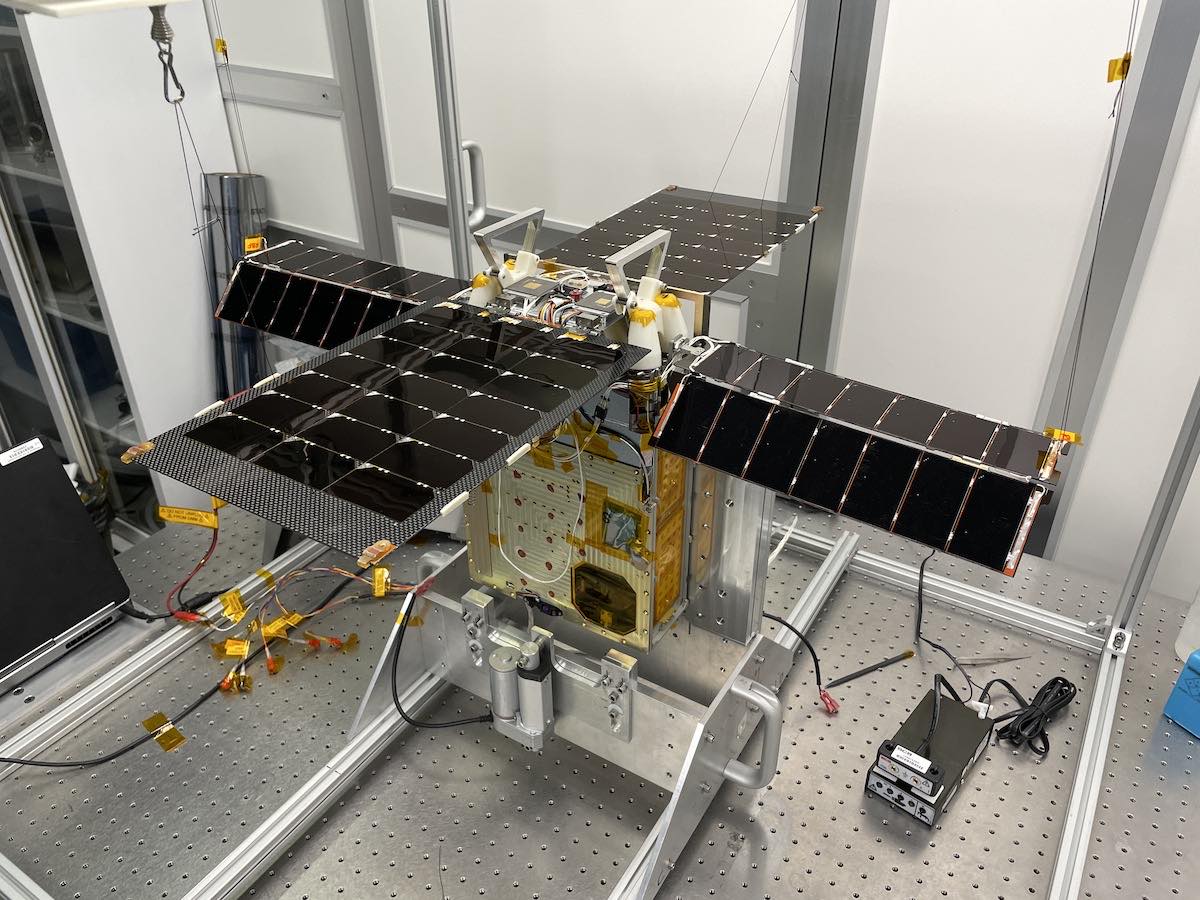

The two other CubeSat projects that missed the deadline for the Artemis 1 were the Cislunar Explorers mission, consisting of a pair of CubeSats from Cornell University, and the CU-E3 mission from the University of Colorado, Boulder.

Neither has secured a new launch opportunity.

The two Cislunar Explorers nanosatellites are designed to orbit the moon and test a water-based propulsion system and optical navigation technology.

Curran Muhlberger, the faculty advisor for the mission at Cornell, said last year that Cislunar Explorers missed its ride on Artemis 1 due to technology development snags and delays caused by the pandemic. Although the team at Cornell was able to assemble and fit-check the spacecraft, Muhlberger said they weren’t confident enough in the system’s reliability to feel comfortable enough to go ahead with the launch on Artemis 1.

In May, Muhlberger said the team has “made good progress” since last year on an integrated simulation of the mission’s propulsion and navigation technologies. “We’re holding off on actively searching for a new launch provider until we complete a rigorous validation of our capabilities,” he said.

Scott Palo, principal investigator for the CU-E3 mission at CU Boulder, said his project suffered multiple failures of flight hardware during testing. “Given our limited resources, we have not yet identified a feasible pathway forward.”

The CU-E3 small satellite was intended to launch on Artemis 1 and head into deep space, reaching a distance more than 2.5 million miles (4 million kilometers) from Earth to test a miniature planar antenna for deep space communications.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.

from Spaceflight Now https://ift.tt/Gn2Mea1

via World Space Info

0 comments:

Post a Comment