EDITOR’S NOTE: Updated June 25 with completion of HPU hot fire test.

With a series of practice countdowns complete, NASA managers said Friday the powerful Space Launch System rocket could be ready for its first test flight in late August or early September to send an unpiloted Orion crew capsule around the moon.

NASA officials said the fourth practice countdown for the SLS moon rocket Monday achieved enough objectives to declare the rehearsals complete, allowing teams to proceed with launch preparations for the Artemis 1 test flight, the first mission of the agency’s Artemis lunar program.

“At this point, we’ve determined that we successfully completed the evaluations and the work that we intended to complete for the dress rehearsal,” said Tom Whitmeyer, NASA’s associate administrator for exploration systems development, who oversees the SLS moon rocket and Orion crew capsule programs.

The 322-foot-tall (98-meter) Space Launch System rocket will roll off its launch pad at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida as soon as July 1, heading back to the Vehicle Assembly Building for a hydrogen leak repair and several previously planned tasks to ready the rocket for flight, according to Cliff Lanham, the senior vehicle operations manager for NASA’s exploration ground systems team in Florida.

The practice countdown Monday marked the first time the Artemis launch team fully loaded both stages of the SLS moon rocket with 755,000 gallons of super-cold liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen propellants. But engineers discovered a hydrogen leak in a quick-disconnect fitting on the bottom of the core stage, in a line that dumps excess hydrogen overboard after running through pipes to condition hardware in the engine section for flight.

The launch team reconfigured software in the countdown sequencer computer to mask the leak, allowing the countdown to continue down to T-minus 29 seconds, moments after control of the countdown handed off to the flight computers on the rocket itself. The rocket’s flight computers halted the countdown when it detected the engines were not ready for ignition, due to the hydrogen leak.

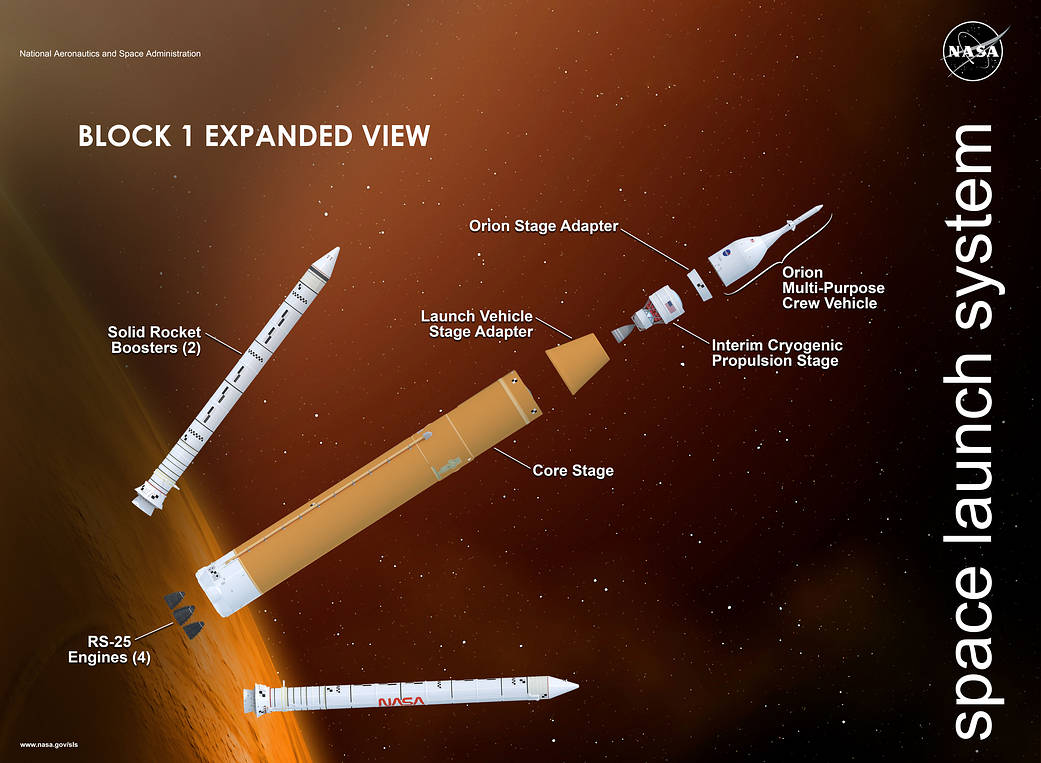

Managers hoped to run through the final 10 minutes of the countdown two times during the dress rehearsal, going as far as T-minus 9 seconds, just before the core stage’s four RS-25 main engines would ignite on launch day. Although the countdown did not get as far as officials hoped, NASA managers decided the test achieved enough goals to move on to final launch preparations.

Phil Weber, a senior technical integration manager at Kennedy, said the test Monday exercised all but 13 of 128 “command functions” engineers wanted to test during the final 10 minutes of the countdown. Most of the others have already been verified in previous testing, he said

Several other technical issues cropped up Monday, beginning with a faulty valve controller in a ground nitrogen gas system in a support facility about a mile from the pad. Technicians replaced the valve assembly, allowing the countdown to proceed after a delay of a couple hours.

Weber said there were also problems with heaters on a liquid oxygen feed line on the core stage. “They turned on, and we tried to control them, and they shut down,” Weber said.

The heaters are used to thermally condition liquid oxygen flowing into the core stage engine section. Weber said engineers believe it’s a “relatively easy” fix for the heaters, adding that the issue is likely a commanding problem, not a hardware failure.

There was also a glitch in a video playback system on the Orion spacecraft, but the launch team could have resolved that problem and continued with the countdown if it occurred on launch day, Weber said. Engineers also looked at data indicating lower-than-expected electrical resistance in a booster steering unit, but additional analysis indicated the reading was not a problem.

The moon rocket’s 4.2-mile (6.8-kilometer) rollback to the Vehicle Assembly Building next week on one of NASA’s Apollo-era crawler-transporters will complete the second stay at pad 39B for the Artemis 1 launcher. The rocket previously rolled to the pad in March for three countdown rehearsals in April, which were cut short by a hydrogen leak and other ground system problems that prevented teams from filling the Space Launch System with cryogenic propellants.

After returning the SLS moon rocket to the VAB, technicals tightened a connection in a liquid hydrogen line between the mobile launch platform and the core stage’s engine section. The hydrogen leak found in April was in a different line than the leaky fitting detected Monday.

Ground teams in May also replaced a balky helium valve on the upper stage, then returned the rocket to pad 39B on June for a fourth practice countdown, or wet dress rehearsal.

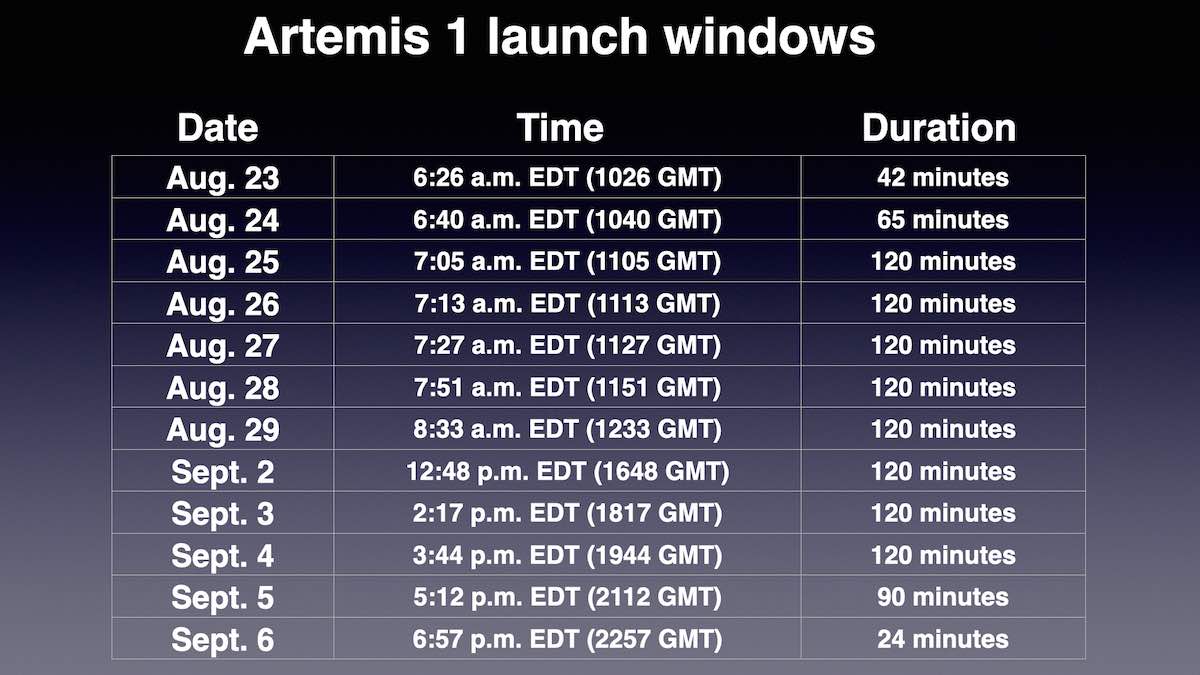

Whitmeyer told reporters Friday that the completion of the countdown dress rehearsal campaign this week could allow the SLS moon rocket to be ready for launch during Launch Period 25, which opens Aug. 23 and runs through Sept. 6. “That’s still on the table,” Whitmeyer said.

Another launch period opens Sept. 19 and extends until Oct. 4, followed by three more two-week launch periods through the end of the year. Depending on when the Artemis 1 mission takes off, the Orion test flight could last roughly 26 days or as long as 42 day. The mission duration hinges on the location of the moon relative to Earth, allowing the Orion spacecraft to complete a half-orbit or one-and-a-half distant orbits around the moon.

The launch periods are constrained by a number of considerations, including the position of the moon in its orbit around Earth, limits on how long the Orion spacecraft can fly in shadow without direct sunlight on its solar arrays, and re-entry and splashdown rules, including a requirement for a daytime return to Earth to aid in recovery operations in the Pacific Ocean.

The launch windows for the Aug. 23-Sept. 6 window are posted below. Aug. 30, Aug. 31, and Sept. 1 not viable launch dates because not all of the launch window constraints are met for those days.

But there’s more work to do for the Artemis ground team before the SLS moon rocket is ready for flight.

One of the milestones not demonstrated in Monday’s rehearsal was the startup of the hydraulic power units on the SLS solid rocket boosters, which should have occurred in the final 30 seconds of the countdown to drive the booster nozzles through a gimbal steering check with their thrust vector control mechanisms.

The hydraulic power units on each booster were hot-fired early Saturday in a successful test of the steering system. Technicians will drain hydrazine fuel from the power units early next week, then move the crawler-transporter under the mobile launch platform ahead of the rocket’s return to the VAB.

Weather permitting, the rollback to the VAB should begin just after midnight local time (0400 GMT) on Friday, July 1, according to Lanham.

Once the rocket is back inside the assembly building, workers will extend 10 sets of access platforms to reach various levels of the launch vehicle, and erect an access stand to reach the leaky hydrogen line. Aside from already-planned work, technicians will replace Teflon seals on quick-disconnect fittings in the tail service mast umbilical, the connection that routes cryogenic propellants between the mobile launch platform and the SLS core stage.

Officials believe one of those seals loosened in the 4-inch quick-disconnect that started leaking during Monday’s countdown rehearsal. Weber, a manager on the Artemis ground operations team, said workers will also likely change out a similar seal on a larger 8-inch propellant fill and drain line as a pre-emptive measure.

Other work inside the VAB will include changing out an avionics box on the SLS upper stage, and a software load on the upper stage computer. The ground crew will also stow final equipment inside the pressurized cabin on the Orion spacecraft, and install flight batteries on the core stage, boosters, and second stage, Lanham said.

“Then, ultimately, we want to do our flight termination system testing, and once that’s complete, we’ll be able to perform our final inspections on all the volumes of the vehicle and do our closeouts,” Lanham said Friday.

The flight termination system consists of pyrotechnic charges on the rocket that would be fired to destroy the vehicle if it veered off course and threatened populated areas.

The ground crew inside the VAB will arm the flight termination system and perform an end-to-end test, demonstrating the ability of the Space Force’s range safety team to send a destruct command to the SLS moon rocket. The flight termination system is only certified for 20 days after completion of the test, and the rocket would need to be hauled back to the VAB to revalidate the destruct mechanisms.

According to Lanham, work on the SLS moon rocket inside the Vehicle Assembly Building will take about six to eight weeks.

Weber said the ground crew will be “hustling” to roll the rocket back to pad 39B after the flight termination system check. The rocket will need to spend 10 to 14 days on the pad before the first launch attempt, and the schedule currently shows the Artemis 1 team could fit in three launch attempts before the 20-day flight termination system certification clock expires.

If the countdown is scrubbed after tanking of the rocket begins, officials will have to wait a few days for another launch attempt, allowing time for replenish cryogenic propellant supplies at pad 39B.

Although the timeline could pave the way for a launch opportunity before the end of August, NASA officials said they are still at least a few weeks away from setting a target launch date, when they have a better idea of how long it will take to complete tasks inside the VAB.

The Space Launch System has been in development more than a decade, costing more than $20 billion to date, making it one of NASA’s costliest programs in that time. NASA plans for the second SLS/Orion flight, Artemis 2, to carry a crew of four astronauts around the moon in 2024, but that hinges on the outcome of the Artemis 1 mission later this year.

Future Artemis flights will include a commercial lunar lander — the first will be provided by SpaceX — to ferry astronauts between the Orion spacecraft and the surface of the moon.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.

from Spaceflight Now https://ift.tt/o6lwvOM

via World Space Info

0 comments:

Post a Comment