STORY WRITTEN FOR CBS NEWS & USED WITH PERMISSION

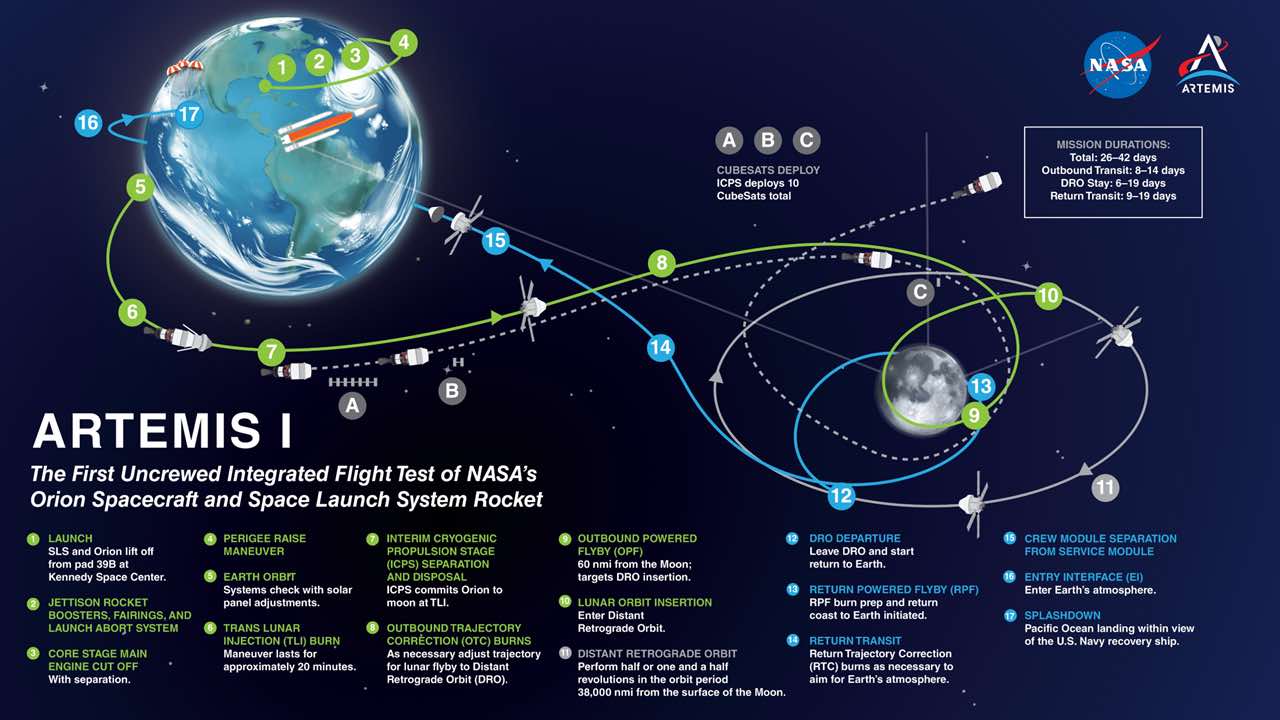

Even using the most powerful rocket NASA’s ever built, getting the agency’s unpiloted Orion spacecraft to the moon for the Artemis 1 test flight won’t be easy. It will hinge on a complex series of precisely orchestrated deep space maneuvers.

Mission planners had to take into account the constantly changing positions of Earth and moon to ensure the Space Launch System rocket accurately delivers Orion to a moving point in low-Earth orbit for the critical “trans-lunar injection” — TLI — rocket firing that will begin the trip to the moon.

They had to design a trajectory sending Orion within a scant 60 miles of the moon’s surface for a flyby that will bend its path out toward the planned “distant retrograde orbit” — one that will carry the capsule farther from Earth than any other human-rated spacecraft.

The trajectory must minimize the amount of time the solar-powered Orion is in the shadow of the moon while setting up a final lunar flyby to precisely target the capsule’s splashdown in the Pacific Ocean during daylight hours as Earth moves through space and rotates on its axis.

All of those factors played into defining a two-hour launch window that opens at 8:33 a.m. EDT Monday when, if all goes well, the 322-foot-tall Space Launch System rocket will blast off from pad 39B at the Kennedy Space Center.

Generating 8.8 million pounds of thrust at liftoff, the SLS rocket will propel Orion, its service module and the booster’s upper stage into an initial orbit, one with a high point, or apogee, of about 1,100 miles and a low point, or perigee, of just 18 miles.

Ten minutes after separation from the SLS core stage but still attached to the Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage, or ICPS, the Orion capsule’s service module, provided by the European Space Agency, will deploy four steerable solar panels to begin recharging on-board batteries.

The ICPS’s single Aerojet Rocketdyne RL10B engine will fire for the first time when the spacecraft nears to high point of the orbit about 51 minutes after launch. The result of the “burn” will raise the low point of the orbit from 18 to about 115 miles.

The SLS’s two-hour lunar launch window is defined by a requirement for the ICPS to reach a point in space on the opposite side of Earth from the moon known as the antipode, where it can fire its engine to break out of Earth orbit and head for the moon.

That point is constantly moving as Earth rotates and moves along its orbit around the sun while the moon moves in its orbit around Earth. The Artemis 1 trajectory is designed so the rocket’s perigee syncs up as required with the antipode so an engine firing can send Orion to a point in space where the moon will be five days later.

At that moment, one hour and 36 minutes after launch, the ICPS’s RL10B engine will fire for 18 minutes, the longest burn ever attempted by that family of engines, increasing the spacecraft’s velocity to some 22,600 mph and effectively raising the high point of the orbit to the vicinity of the moon.

A half hour after the TLI engine firing, the Orion capsule will separate from the ICPS to fly on its own. From that point, the ICPS will continue toward the moon — deploying a dozen small scientific research satellites, called CubeSats, along the way — before thruster firings to head out into a “disposal” orbit around the sun.

Orion flight controllers, meanwhile, will test the orbital maneuvering system engine powering the capsule’s service module, carrying out four trajectory correction maneuvers. Those will set up a critical “outbound powered flyby” engine firing.

“That’s the big burn that will actually move Orion and send it toward the planned distant retrograde orbit (around the moon),” said lead Flight Director Rick LaBrode. “So when we do that burn and we go by the moon, we’re going to be about 60 miles off the surface. It’s going to be spectacular.”

The outbound powered flyby will occur over the back side of the moon when Orion is out of contact with mission control.

“So we’ll be praying and I’ll hold my breath,” LaBrode joked. “But (we’re) confident that all will go well.”

After a slingshot-like loop around the moon, another burn will put the craft in the planned distant retrograde orbit.

Cameras inside and out

Throughout the flight, cameras inside and outside Orion will document the view, beaming back selfies and shots of the spacecraft, moon and Earth, including planned views of Earthrise over the limb of the moon reminiscent of a famous shot from the Apollo 8 mission that came to symbolize the environmental movement.

All the while, flight controllers will be testing Orion’s systems and collecting a steady stream of engineering telemetry to document the spacecraft’s performance in the deep space environment. The service module will be closely monitored given the Artemis 1 mission will last twice as long as the module’s 21-day design certification.

“We’re doing public affairs outreach where we maybe maneuver, do a selfie of Orion with the moon in the background or the or the Earth in the background,” LaBrode said. “We’re going to try and catch the Earthrise. That’s a spectacular image.”

On September 8, Orion will be farther from Earth than the record set by the Apollo 13 crew — 248,654 miles — as it flies through one-and-a-half laps around the moon in that distant orbit.

The long journey home

The trip home will begin on September 21 when the service module engine fires again to break out of the distant retrograde orbit and loop back toward the moon. Three days later, thanks to the changing geometry of Earth, moon and spacecraft, Orion will reach its maximum distance from Earth at 280,000 miles.

On October 3, the service module engine will fire again as Orion makes another lunar flyby, this one at an altitude of about 500 miles. The “return powered flyby” burn will ensure Orion re-enters Earth’s atmosphere at the precise point needed to enable a daylight Pacific Ocean splashdown 50 miles or so west of San Diego.

If all goes according to plan, Orion will get back to Earth on October 10. Twenty minutes before atmospheric entry, the capsule will separate from its no-longer-needed service module and orient itself so its 16.5-foot-wide heat shield is facing the direction of travel.

The capsule then will slam into the top of the discernible atmosphere at an altitude of 400,000 feet while moving at nearly 25,000 mph. The spacecraft will dip into the atmosphere to slow down, then pop back up like a rock skipping across a lake. It will enter a second time moments later, enduring temperatures of up to 5,000 degrees as atmospheric friction slows the craft to a velocity of around 300 mph.

“We’re actually doing what’s called a skip entry profile,” entry Flight Director Judd Frieling explained. “So we’ll hit entry interface at 400,000 feet and then we’ll immediately start to control the lift vector of the capsule such that we dip a little bit in the atmosphere and then we come back up a bit and then back in. Once we get out of that second period, we will continue our journey towards our splashdown site.”

Orion will jettison a parachute bay cover at an altitude of 35,000 feet using 3 small chutes that will, in turn, pull out two 23-foot-wide drogue parachutes that will stabilize the spacecraft and help it slow down to about 130 mph.

Three 11-foot-wide pilot chutes then will deploy, pulling out the capsule’s three 116-foot-wide main parachutes at an altitude of about 6,800 feet. The mains will slow the descent to a relatively gentle 17 mph for splashdown.

Expected mission duration at splashdown: 42 days, 3 hours and 20 minutes.

“Once we’ve splashed down, we’ll leave the vehicle powered for about two hours,” Frieling said. “We’re going to do some testing there, thermal testing, to make sure that we have adequate cooling for astronauts when we do eventually have them on board and are waiting to be picked up by the recovery crews.

“And then, after that two-hour period, we will power down the vehicle and we’ll hand (it over) to the recovery team that’s there on a Navy boat.”

A joint Navy-NASA recovery team based on the USS Portland will collect the main and drogue chutes before attaching cables and towing Orion into the ship’s well deck, a sort of enclosed dry dock that can be flooded or pumped dry.

Orion will be towed into the flooded chamber and positioned above a mounting fixture. As water is pumped out, the capsule will settle onto the fixture for shipment back to U.S. Naval Base San Diego and, from there, to the Kennedy Space Center for a detailed inspection.

from Spaceflight Now https://ift.tt/Y5ua7yN

via World Space Info

0 comments:

Post a Comment