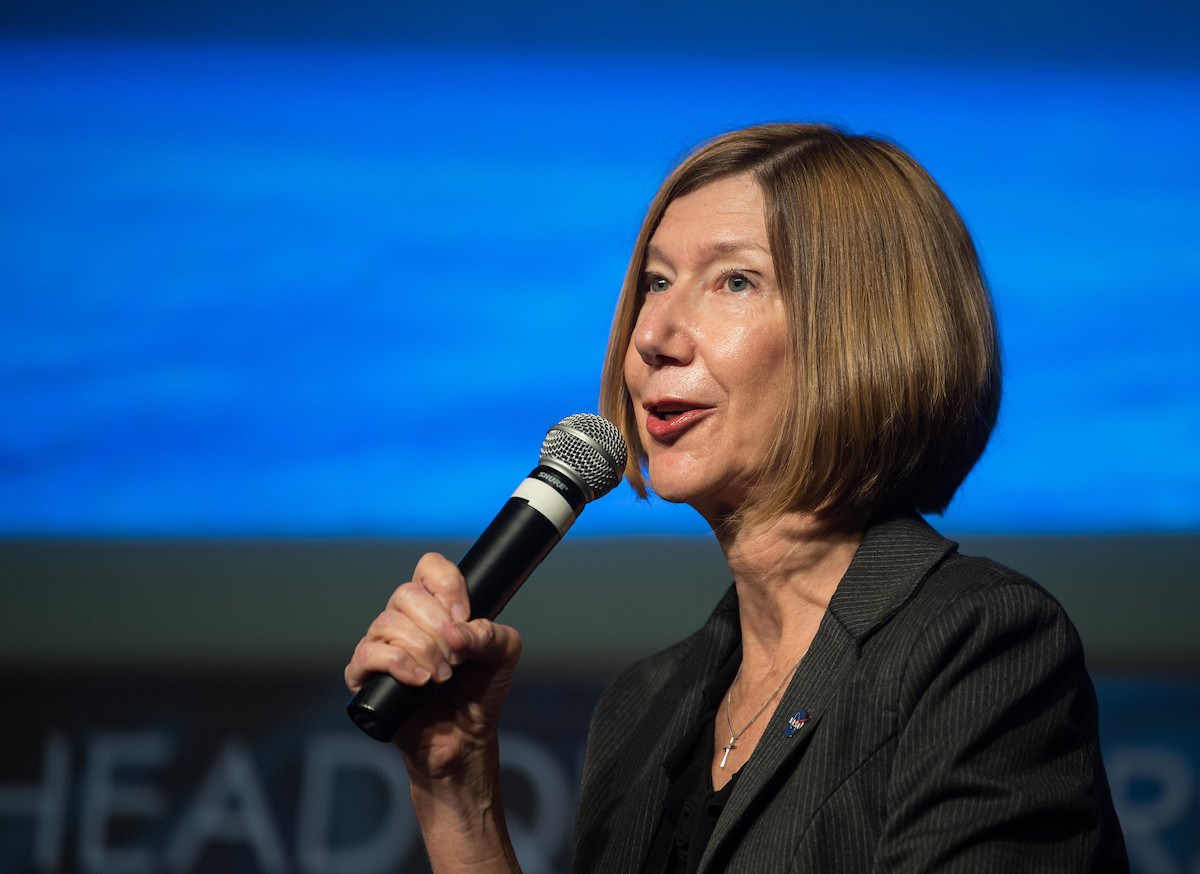

Kathy Lueders, head of NASA’s human spaceflight operations division, said Monday that joint activities on the International Space Station are continuing amid Russia’s attack on Ukraine, including preparations for the return of NASA astronaut Mark Vande Hei to Earth on a Russian Soyuz spacecraft March 30.

While operations aboard the station — and joint U.S.-Russian training for future expeditions — have not been impacted by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Lueders said NASA is pursuing more “operational flexibility” to add new capability to the U.S. side of the complex.

“We are not getting any indications at a working level that our counterparts are not committed to ongoing operation of the International Space Station,” Lueders said Monday. “We, as a team, are operating just like we were operating three weeks ago.

“Our flight controllers are still talking together, our teams are still talking together, we’re still doing training together, we’re still working together,” she said. “Obviously, we understand the global situation where it is, but, as a joint team, these teams are operating together.”

Four U.S. astronauts, two Russian cosmonauts, and a European Space Agency flight engineer are currently living and working aboard the station as it flies around Earth every hour-and-a-half at an altitude of more than 250 miles (400 kilometers).

Three of the crew members — the two Russians and one American — are scheduled to return to Earth on March 30 on Russia’s Soyuz MS-19 spacecraft. Russian command Anton Shkaplerov, flight engineer Pyotr Dubrov, and NASA astronaut Mark Vande Hei are due to land in Kazakhstan on the Soyuz capsule.

Russian recovery teams will be on standby in the landing area to help the crew members out of the spacecraft. Vande Hei and Dubrov will close out a 355-day expedition in orbit, enough for Vande Hei to set a new record for the longest duration spaceflight by a U.S. astronaut.

The return of the Soyuz MS-19 spacecraft March 30 will follow the launch of three fresh Russian cosmonauts on the Soyuz MS-21 mission March 18. Russian commander Oleg Artemyev will lead the three-man crew on a six-month mission on the space station.

Lueders said NASA and Roscosmos — Russia’s space agency — are pressing ahead with the scheduled return of Vande Hei and his Russian crewmates in late March.

“We … are getting ready for Mark to return, and all of the normal operations are in place for that, for us to be able to go do that,” Lueders said. “As always, if you’re working on space station, you continue to monitor the situation and operate.”

Joint U.S.-Russian crews have landed on Soyuz spacecraft numerous times before, and Russia provided the only crew transportation capability to the space station between the retirement of NASA’s space shuttle fleet in 2011 and the first astronaut flight on SpaceX’s Crew Dragon capsule in 2020.

Lueders was speaking in a press conference with Axiom Space, a Houston-based company planning to fly the first purely commercial mission to the International Space Station. Commander Mike Lopez-Alegria, a retired NASA astronaut and now an Axiom employee, will fly to the station on a SpaceX Crew Dragon spacecraft with three paying passengers for a 10-day mission scheduled for launch from Kennedy Space Center on March 30.

After flying a series of commercial astronaut missions, Axiom is planning to build and launch a commercial module to link up with the International Space Station, providing private living quarters and lab resources for visiting crews and clients. Eventually, Axiom wants to detach its modules from the space station to create a standalone orbiting research complex, a privately-owned outpost the company says could be ready in 2028.

NASA officials have said the agency is not currently considering the possibility of Mark Vande Hei returning to Earth on Axiom’s mission — known as Ax-1 — a move that would require one of Axiom’s customers to give up his seat on the Crew Dragon capsule.

After the Axiom mission, another SpaceX crew capsule is scheduled to lift off April 15 with three NASA astronauts and an ESA astronaut to begin their own half-year expedition on the space station with the three Russian cosmonauts launching March 18. The astronauts launching April 15 on SpaceX’s Crew-4 mission — under contract to NASA — will replace an outgoing team of astronauts due to return to Earth on their own Crew Dragon spacecraft in late April.

Lueders said space station operations have persevered through diplomatic crises before.

“We have operated in these kind of situations before, and both sides always operated very professionally and understands, at our level, the importance of this fantastic mission and continuing to have peaceful relations between the two countries in space,” she said.

NASA wants to extend the life of the International Space Station until 2030, allowing more time for U.S. industry to develop new commercial space stations in low Earth orbit, a region of space a few hundred miles above the planet. Once a private space station is operational, NASA wants to book rides to the complex for its astronauts as needed on a commercial basis, rather owning and managing the entire program.

The U.S. space agency also wants more time with the International Space Station to demonstrate new technologies for future missions to the moon and Mars.

Although NASA officials report no near-term impacts to the station’s operations, it remains to be seen how the Russian invasion of Ukraine might affect the program’s planned life extension until 2030.

With SpaceX’s Crew Dragon spacecraft now operational, and Boeing seeking to have its delayed Starliner spaceship ready for astronauts within a year, NASA’s work on the space station is less reliant on Russia’s space program than at any point in the last decade.

But the U.S. and Russian segments of the space station remain interconnected, by design.

NASA and Roscosmos are the two largest partners on the International Space Station, which could not easily operate without critical contributions from U.S. and Russian modules. The U.S. segment of the station generates the bulk of the lab’s electrical power and maintains the pointing of the complex in orbit.

Russia’s modules and Progress supply ships are the primary source of propulsion, maintaining the lab’s altitude and occasionally steering the space station out of the way of space debris. Russia is also planning to oversee the de-orbiting and disposal of the huge station — the largest spacecraft ever put into orbit — into the unpopulated ocean at the end of its service life, currently expected around 2030.

A Northrop Grumman Cygnus cargo freighter that arrived at the space station last week will debut a new U.S. capability to reboost the orbit of the complex. But the Cygnus spacecraft is not intended to maneuver the space station away from space junk, or make major orbit adjustments.

“We always look for how do we get more operational flexibility, and our cargo providers are looking at how do we add different capabilities,” Lueders said. “Northrop Grumman has been offering up a reboost capability, and our SpaceX folks are looking at can we have additional capability.

“It would be very difficult for us to be operating on our own,” she said.

The space station was created with “joint dependencies,” she said. “It’s a place where we live and operate in space in a peaceful manner. That’s really a model for us to be operating in the future.

“It would be a sad day for international operations if we can’t continue to peacefully operate in space,” Lueders said. “And, as a team, we are doing that.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.

from Spaceflight Now https://ift.tt/bex8tTc

via World Space Info

0 comments:

Post a Comment