Astra, a company seeking to carve out a segment of the growing small satellite launch market, test-fired its two-stage rocket at Cape Canaveral on Saturday in preparation for an upcoming demonstration flight for NASA.

The engine test-firing, called a static fire test, occurred on launch pad 46 at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station as Astra prepares to deliver four small CubeSat nano-satellites into orbit under contract to NASA’s Venture Class Launch Services program.

The rocket’s five Delphin engines, burning kerosene and liquid oxygen propellants, fired for less than 10 seconds at 11:40 a.m. EST (1640 GMT) Saturday on pad 46.

The static fire test sent an exhaust plume away from the rocket that was visible from public viewing locations several miles away. A low rumble was also heard from the beaches south of Cape Canaveral.

Astra confirmed the static fire test in a tweet Sunday afternoon. Chris Kemp, Astra’s founder and CEO, tweeted that the company will announce the target launch date and time for the mission after receiving a launch license from the Federal Aviation Administration.

The static fire test was expected to be a prerequisite for Astra receiving an FAA launch license.

Astra’s rocket is small in size compared to other launch vehicles that regularly fly from Cape Canaveral. The launcher, called Rocket 3.3 or LV0008, stands just 43 feet (13.1 meters) tall, more than five times shorter than SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket, and about the same height as the Falcon 9’s payload compartment.

The commercially-developed launch vehicle, in its existing configuration, is designed to carry a payload of around 110 pounds (50 kilograms) into a 310-mile-high (500-kilometer) polar orbit, according to Kemp. Astra’s rocket is sized to offer dedicated rides to orbit for small commercial, military, and research satellites.

Astra launched its first successful mission to low Earth orbit in November from Kodiak Island, Alaska, on a test flight sponsored by the U.S. Space Force, following three previous launch attempts that faltered during the climb into orbit.

Founded in 2016, Astra aims to eventually conduct daily launches with small satellites at relatively low cost, targeting a smallsat launch market cramped with competitors such as Rocket Lab, Virgin Orbit, and Firefly Aerospace, each of which has begun flying small launch vehicles. Numerous other companies are months or years away from debuting their smallsat launchers.

Four CubeSats are set to ride the rocket into orbit on a mission arranged by NASA.

The mission is part of NASA’s Venture Class Launch Services, or VCLS, program, which awarded Astra a $3.9 million contract last year for a commercial CubeSat launch. Scott Higginbotham, head of NASA’s CubeSat Launch Initiative at Kennedy Space Center, says the agency is the sole customer for the upcoming Astra launch.

The Venture Class Launch Services program is aimed at giving emerging small satellite launch companies some business, while helping NASA officials familiarize themselves with the nascent industry.

NASA previously awarded VCLS demonstration missions to Rocket Lab and Virgin Orbit, which completed their first launches for the U.S. space agency in 2018 and 2021. The U.S. military has awarded similar demonstration launch contracts to Astra and other companies.

Higginbotham said the VCLS mission gives NASA insight into companies’ management and technical teams, procedures and processes, and their hardware designs.

“That’s going to allow us to be a better consumer going forward if they stay in business, and can offer their services to us later on,” Higginbotham said. “We’ll already have been introduced and have done a deep dive, of sorts, into those companies to understand what makes them tick, and that’s that’s of tremendous value to us.”

The VCLS demo missions are also a stepping stone toward certification of the new smallsat launchers to carry more expensive NASA satellites into orbit. The certification isn’t required for the demo missions themselves.

“NASA has other missions that require a little bit more reliability from the launch vehicle, a little more certainty, and a little more launch vehicle insight,” Higginbotham said.

A team of fewer than a dozen technicians and engineers set up Astra’s rocket on pad 46 earlier this month. Astra’s launch control team remained behind at the company’s headquarters in Alameda, California, where managers remotely control the rocket’s countdown.

A fueling test, or wet dress rehearsal, was accomplished earlier in January before Saturday’s static fire.

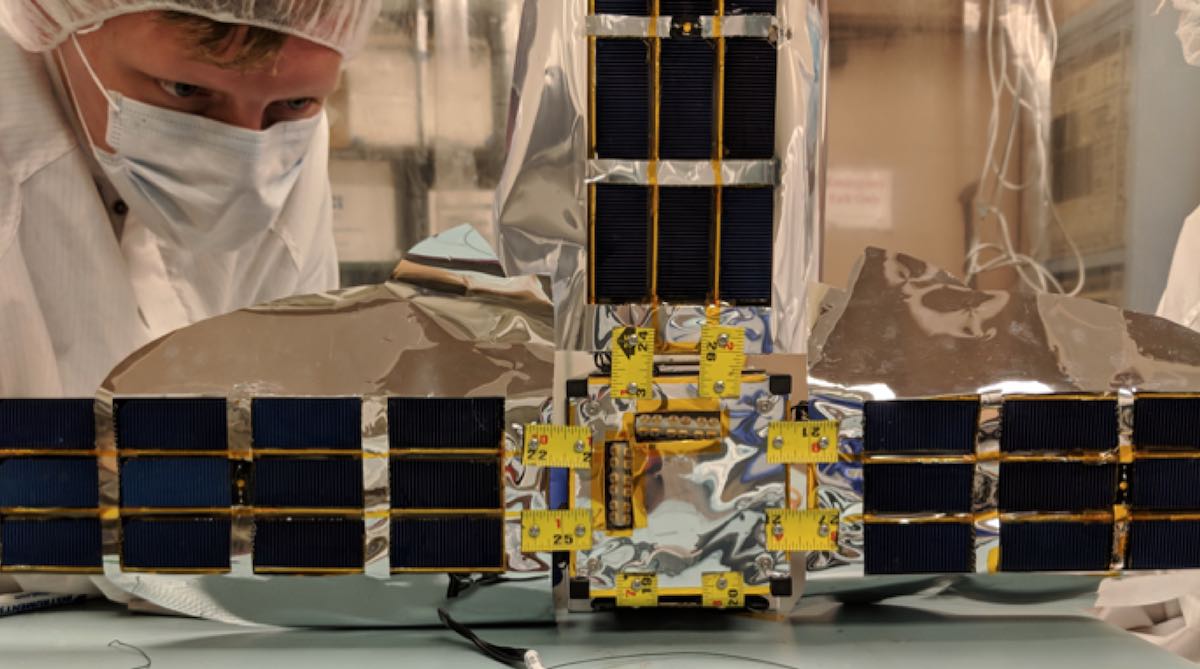

NASA assigned four nano-missions to the Astra demonstration launch through the agency’s CubeSat Launch Initiative program.

One of the CubeSats was developed by the University of California, Berkeley. Named QubeSat, the small spacecraft will test a tiny gyroscope, a device used to help determine the orientation of satellites in space.

Data from INCA will “contribute to understanding the radiation environment that satellites encounter, and to the understanding of neutron air showers, which pose a radiation hazard to occupants of high-altitude aircraft such as airliners,” according to the student team that developed the mission.

The BAMA 1 mission, developed at the University of Alabama, will demonstrate a drag sail device designed to help old satellites and space junk drop out of orbit. The drag sail will encounter air molecules from the rarefied atmosphere at the satellite’s altitude, slowing its velocity enough to fall back to Earth.

The final payload is a CubeSat named R5-S1 from NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston. NASA says the mission’s objectives including demonstrating quick CubeSat development and testing technologies useful for in-space inspection, which could make human spaceflight safer and more efficient.

Another CubeSat mission from UC-Berkeley originally selected by NASA for the Astra demonstration launch wasn’t ready in time for integration with the rocket in December, according to Jasmine Hopkins, a NASA spokesperson at Kennedy Space Center.

The CubeSat Radio Interferometry Experiment, or CURIE, mission, consists of two identical three-unit CubeSats, each the size of a shoebox, with radio antennas to detect emissions from solar activity, such as solar flares and coronal mass eruptions.

NASA will assign the CURIE satellites to another launch, Hopkins said.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.

from Spaceflight Now https://ift.tt/3GU7bTJ

via World Space Info

0 comments:

Post a Comment